Watch again: Live Lesson video clips

This set of shorter video clips is taken from the Live Lesson programme and can be used to teach individual topics.

Taste

Barney, Male Presenter:

What happens when we eat? Well if we divide today's lesson into three stages, the first stage we're going to look at is taste. And I can't wait for this, cause this is going to go into my face.

Fran, Female Presenter:

We'll see. We'll see because as you guys know, taste is one of our senses.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Yes.

Fran, Female Presenter:

And we use taste when we eat food. obviously!

Barney, Male Presenter:

We do. Yes.

Fran, Female Presenter:

But it's not just about taste. Our other senses, like sound, touch, smell and sight, come into play as well. And some foods look nicer than others to eat, don't they audience?

Barney, Male Presenter:

That's true.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Yeah?

AudienceYes.

Barney, Male Presenter:

They're all staring at the chocolate cake right now, going yeah.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Well, let's see which one they prefer. If you would prefer this nice colourful salad, just by looking at it, make some noise now.

Audience:

Yes. [LAUGHS]

Fran, Female Presenter:

Not so much.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Okay, well let's try this one, shall we? Make some noise if you would like this dark, velvety, succulent, sweet, sugary, runny, chocolate mess of a cake.

Audience:

[SHOUTS] Yeah.

Barney, Male Presenter:

How surprising a finding that was.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Yeah, I think the cake might have won slightly there. But I wonder how many of you went for it, just because it looks nicer than the salad. But we could also go for foods that make noise, like crisps. Just the sound of someone annoyingly munching crisps, can make them actually appeal to some of us.

Barney, Male Presenter:

It's very true. Also, how food tastes can influence what we choose to eat in the first place. You might like savoury foods more than you like sweet things.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Hey, did you bring any meat paste cocker? I want some paste, I want to rub into my face.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Of course not, it's disgusting. What do you want that for?

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

You can't get the staff, cocker.

Barney, Male Presenter:

You really can't.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Okay, so we haven't got you any meat paste, but what we do have is this. Now everybody take a look at this very special box, which your school should have received from Terrific Scientific, to help you conduct your own investigation. This box is going to help you unleash your inner scientist. And inside of this box, amongst other things, is some blue food dye. And this will help you discover what kind of taster you are and see if you are either a non-taster, a taster or a super taster.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Okay, well I think I'm a super taster, cause I can taste everything. And it tastes super.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Okay.

Barney, Male Presenter:

But how do I find out for sure?

Fran, Female Presenter:

Well, Barney, you need to stick your tongue out.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Well I was told that was very rude when I was little. You can't just stick your tongue out like that on telly.

Fran, Female Presenter:

And when have you done anything that you're told?

Barney, Male Presenter:

Never.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Exactly! So what I'm going to do is I'm going to put some blue food dye on it and what I'm looking for, is for the number of fungi-form papillae.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Oh yes the fungi-formius pappilonius.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Yes the fungi-form papillae. Which are like the pink lumps and bumps. And we're looking to see how many of those you have…

Barney, Male Presenter:

On my tongue?

Fran, Female Presenter:

…in a certain area of your tongue.

Barney, Male Presenter:

I've got crisps on my tongue at the minute.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Well, we'll see what happens, cause I'm going to look at it through this ring and see how many you have within that ring.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Okay. Good.

Fran, Female Presenter:

And if you have nought to five papillae, then you're a non-taster.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Yes.

Fran, Female Presenter:

If you have six to 10 papillae, that means you're a taster.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Papillae is a funny word isn't it?

Fran, Female Presenter:

Papillae, yes. And that means you're one in two of us are that. That's most common.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Okay.

Fran, Female Presenter:

But if you have 11 or more papillae, then you're a super taster.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Okay. Well while Fran tests me, here's a short explanation as to how the blue food dye test works.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Alright, stick your tongue out.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Okay.

Audience:

Papillae.

Narrator:

All our taste buds sit in little bumps on our tongue called fungi-form papillae. To count how many you have, you apply some blue food dye to the front third of your tongue using a cotton bud like this. Your tongue will go blue, but the dye will slide off the fungi-form papillae, making then look like large pink bumps. Using a piece of hole-punched card, you can now count how many papillae you have within the small circle and compare it to our taste chart.

Fran, Female Presenter:

You alright there, Barney yeah?

Barney, Male Presenter:

Yeah.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Yeah, yeah. Alright. Now the thing is, it's time to give the results of Barney's tongue, let's have a look. Okay, well Barney you are actually a taster.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Oh amazing!

Fran, Female Presenter:

So statistically, you're the same as half of the population and you have an average amount of fungi-form papillae on your tongue.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Which means that I'm a taster.

Fran, Female Presenter:

It does mean you're a taster.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Well I'm going to take my tasty taster over here with my blue tongue. Cause it's such a simple test, you can learn so much from it as well. Lots of you been doing this in your classroom, since you got the box. And you've already sent us your results. So have a look at these great pictures that have been sent in. Braunstone Community Primary school in Leicester, that's a good way to hold your chin up if you're being tested. Beautiful! Dunrossness Primary School, Shetland, they're doing their blue tongue test. He's very interested in counting the fungilonius papilonius. New Scotland Hill Primary School in Berkshire, this is actually a very clever photograph, because they've arranged themselves in order of super taster at the left to taster in the middle and non taster on the right. That's a really clever idea, that is. If we take a look here at the Duloe C of E School in Cornwall, they're doing the same thing and as you can see, they wear lab coats instead of uniforms. So thank you.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Well I've never seen quite so many papillae.

Barney, Male Presenter:

I've never seen so many pallilius in my life.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Not that.

Barney, Male Presenter:

I keep saying it wrong, by the way. Don't listen to me, I'm just here to ask questions today. Now we've got a little bit of a graph for you, because we can now reveal for the very first time, how many of you are super tasters, on our charts. Now thousands of you have already been doing this test and sending in your results. So let's take a look at them here. Wow! 39% are super tasters. That's quite a high number that, isn't it?

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Yes.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Now you'll notice here, the teachers have already spotted this, I'm sure. But this is not just a chart, it's a pie chart. And it's a pie chart because we're talking about food, we're eating and taste-- get it? It's a pie…

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Barney?

Barney, Male Presenter:

What?

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

I do the funnies, cocker.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Sorry.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Now did you know that dogs have got taste buds too, you know?

Barney, Male Presenter:

Have they?

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Yeah, most animals do actually. Dogs have got about 1,700 of them.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Yeah.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Would you like to look at my papillae?

Barney, Male Presenter:

Sure. Okay.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Touch them. Touch them.

Barney, Male Presenter:

I don't really want to. I don't want to touch them really.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Touch them.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Okay,okay. It's quite smooth as a surface isn't it?

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Oh, Barney.

Barney, Male Presenter:

What have you been eating?

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Most things.

Barney, Male Presenter:

It's just one big papillonius that isn't it?

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

I've got one big papillae.

Barney, Male Presenter:

I can trade your knowledge for some other knowledge.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Can you?

Barney, Male Presenter:

I can talk to you about birds. Did you know that birds have fewer taste buds than humans and they actually have a poor sense of taste. Flies, and butterflies, can taste with their feet. Now think about what flies land on.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Ugh! Is that why they don't wear shoes?

Barney, Male Presenter:

It must be. But you are right about dogs. They do have about 1,700 taste buds, but that is nothing…

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

I told you that.

Barney, Male Presenter:

…you did, but I've got to read it again.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Alright.

Barney, Male Presenter:

But that's nothing compared to the 10,000 taste buds that we human have.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

Oh you're just showing off now.

Barney, Male Presenter:

10,000 we have.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

You keep your extra taste buds. Hey, do you know something Barney?

Barney, Male Presenter:

What's that?

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

I'm supposed to be man's best friend.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Yeah.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

But right now, I'm not feeling the chemistry between us. Yet more science jokes, cocker. I use that joke in the last live lesson.

Barney, Male Presenter:

It's funny yeah.

Voice of Hacker, Puppet dog:

And they've invited me back. And I didn't even put my feet up.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Yeah, yeah. Oh, alright thanks Hacker. Now we've just talked a bit about how your taste buds can define what kind of taster you are. But, we're about to learn if it's possible to change your taste to enjoy bitter foods more than you did before. Now, back in November, Terrific Scientific teamed up with Coventry University and investigated the taste buds of children in four schools, from Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland and this lot from England. Give us a cheer?

Audience:

[SHOUTS]

Fran, Female Presenter:

Feast your eyes on this.

Plymouth Grove Shcool Teacher:

We're really lucky because we're going to be taking part in a really exciting science experiment for Terrific Scientific. It's going to be all about taste.

Female pupil:

I like carrots.

Male pupil:

Chicken nuggets.

Female pupil 2:

Sweetcorn.

Male pupil 2:

Pizza.

Male pupil 3:

I don't like peas.

Female pupil 3:

Sprouts.

Female pupil 4:

Tomatoes.

Female pupil 5:

I hate broccoli.

Male pupil 4:

Broccoli, cabbages and most vegetables.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

What we're hoping to do in this experiment is to see can we learn to like a vegetable that we would normally reject?

Plymouth Grove Shcool Teacher:

So, we've got two things to try today. And one of the things that you're going to try is kale.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

The reason we've chosen kale, is it tastes quite bitter and lots of people don't like it.

Plymouth Grove Shcool Teacher:

And one of the things you're going to try today is raisins. [SHOUTS]

Professor Jackie Blissett:

A raisin is really acting as the control in this experiment. We need to see whether just taking part in a study might make a difference to what you prefer.

Male pupil 3:

I've never eaten kale, this is the first time.

Male pupil:

It taste really, tasted like a sock a little bit.

Female pupil 2:

It was quite crunchy and I didn't expect that.

Male pupil 5:

I didn't really like the kale but I liked the raisins.

St. Fagan's Primary Male Teacher:

After day one, we split into two groups. One group got the raisin and the other group got the kale and since then we've been tasting that every day.

Male pupil 3:

Today I liked it because it wasn't too bad.

Female pupil 4:

On the first day, I like it. And now every time I eat it, it's getting better.

Female pupil 6:

It's weird texture. It tastes like paper.

Hazel Wood Primary male teacher:

Today is the final day you get the chance to taste the kale. [SHOUTS]

Male pupil 7:

On the first day, I didn't really like it that much. But now I really like it.

Male pupil 8:

At the start, I thought it was okay and then, as it's gone on, it got a wee bit worse and then it got a bit okay.

Male pupil 4:

I got used to it and I started to quite liking it more.

Male pupil 9:

After three weeks I still didn't like the kale.

Hazel Wood Primary male teacher:

Today we're going to try and find out if there are any super tasters in the class.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

We're also interested in whether or not the number of taste buds that you have on your tongue, might make a difference to how easy it is for you to learn to like these bitter tasting vegetables.

Female pupil 4:

I had 16 taste buds on my tongue. And that means I am a super taster.

Male pupil 10:

I had 18.

Female pupil 7:

I had 10 but I'm in between a super taster and a non taster.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

What I'd like pupils to take from away from this experiment, is a love of science and a bit of an understanding of what it might take to carry out a scientific experiment.

Female pupil 4:

It has been really fun to be part of such a fantastic experiment.

Audience:

[SHOUTS]

Barney, Male Presenter:

That was clever wasn't it? So, over three weeks, four school tasted kale and raisins. The investigation was recorded by the school teachers and sent away to Coventry University, where scientists look for any patterns in the results. And the results which were revealed this morning on BBC Breakfast news. So here to tell us more about those results and the investigation is the brains behind it, she was in the film, please give a huge round of applause for Professor Jackie Blissett.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Woo! [SHOUTS]

Barney, Male Presenter:

Jackie, hello. Welcome.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Hi there, hi.

Barney, Male Presenter:

So let's talk about the aim of the investigation. What were you trying to find out?

Professor Jackie Blissett:

So what we were trying to do with this study was to see whether we could learn to like kale, which is quite a bitter tasting food and one that often people don't like very much. Just by trying a little bit of it every day, for three weeks. We were also interested in whether or not it might be more difficult to learn to like that bitter taste if you are a super taster.

Barney, Male Presenter:

And we had quite a high number of super tasters on our pie chart. Is that higher than you'd expect on there?

Professor Jackie Blissett:

It was, yeah. So we would expect around 25% of the population to be super tasters.

Fran, Female Presenter:

So about a quarter?

Professor Jackie Blissett*:

About a quarter. There are lots of reasons why we could have got a high number of super tasters. One of the things that could have happened, is that we could have had children with a low number of fungi-form papillae in our original sample, where we decided what the cut offs were.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Yeah.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

It could have been that children were counting other bumps on the tongue that weren't fungi-form papillae. Or it could be to do with where people are from or their age or their gender, which we know affects their taste sensitivity.

Barney, Male Presenter:

So would that fit with this message from Mr. Dellafield at St. Luke's Primary School in Worksop. Uh we had 44% super tasters.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Wow!

Barney, Male Presenter:

Many children made comments such as who is winning and I suspect the counting may have skewed to be slightly higher.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Yeah, so that's what we call bias in an experiment, isn't it?

Barney, Male Presenter:

Right.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

That people wanted to be super tasters, so they may have been inclined to count a few more paps.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Who wants to be a super taster in here? Hands in the air. Every single person, course it does.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Yeah. You don't get a cape.

Barney, Male Presenter:

No.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Yeah, see I don't know if I want to be super taster. I like to enjoy all the food.

Barney, Male Presenter:

I do. That's a good point.

Fran, Female Presenter:

So if you are a super taster, does it mean that you like certain foods more or less?

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Well actually, what it means, usually, is that you like quite a few foods less than other people. And those tend to be the really strong flavoured foods, particularly the bitter tasting foods, like Brussels sprouts…

Barney, Male Presenter:

yuk!

Professor Jackie Blissett:

…or kale like we had in this experiment. Coffee or even things like chilli and things that have a kind of burn in the mouth.

Fran, Female Presenter:

I get you. I get you.

Barney, Male Presenter:

My favourite foods.

Fran, Female Presenter:

Yeah. So, do you get right and wrong answers in experiments like this?

Professor Jackie Blissett:

There's no right or wrong answer in an experiment like this. We set up our experiments to test the ideas that we have. Sometimes those experiments support what we think we're going to find. And sometimes they don't. We always have to look at our data and think about the experiment to explain the results that we get.

Barney, Male Presenter:

It always has to be a fair test as well doesn't it? How do you make that fair?

Professor Jackie Blissett:

It does always have to be a fair test. So we did lots of things in this study to try and make it a fair test. One of the things we did was to have what we call a control group. So the children who ate raisins every day were doing that because we wanted to know whether just taking part in the study might make a difference to how you rated the kale at the end. The other important thing is the only thing that was different between our control group and our experimental group was whether or not they had kale every day. And also, we tossed a coin to decide whether or not children should be in the kale group or the raisin group…

Barney, Male Presenter:

Okay.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

…because it wouldn't have been a fair test if you could have chosen which group to go into.

Barney, Male Presenter:

So let's ask the question then about the experiment, you've got the results, can you actually train your taste buds to like a taste?

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Well the good news is, you can train yourself to like something more than you liked it before. You're not really training your taste buds, but what we found in this experiment, was that the children who had a little bit of kale every day, were significantly more likely to like it at the end of the study, than the children who had raisins every day. The thing is, that what's going on, it's not about changing your taste buds, it's your brain learning about the flavour of the food, from it's taste, it's smell and learning that it's safe to eat.

Barney, Male Presenter:

Amazing.

Taste

Professor Jackie Blissett tells us what it means to be a super taster in this clip from the Live Lesson.

Food

Fran Scott:

Now we're going to discover what happens to our food once we've eaten, and explore what we need from the food in order to help us function

Barney Harwood:

I know what I need from my food. I want to eat it, I want it to taste good, and I want a full belly at the end of it.

Fran Scott:

Of course you do, and you are right, that's what most people want. But it's also important to have a balance in the range of food that we eat. We want to have food that gives us energy

Barney Harwood:

Yes.

Fran Scott:

That keeps us healthy.

Barney Harwood:

Yes

Fran Scott:

Makes us grow, and even repairs our body. So what we need from food are nutrients in order to make all those things happen.

Barney Harwood:

Okay, well let's talk about nutrients then. What are they? How many are there?

Fran Scott:

The main nutrients are proteins, carbohydrates, fats and vitamins and minerals. Some foods contain one, some or all of these things. What we need to think about is how much we need of the different nutrients.

Hacker T Dog:

Hey Scott, Frank. Frank, Scott, animals need nutrients too, don't we Fran?

Fran Scott:

You do need nutrients. But to be fair, you need the fats, the proteins, the carbohydrates and the vitamins and minerals, but how many you need depends on what sort of size of dog or animal you are, and how much you do, so how much energy you need.

Barney Harwood:

Yeah.

Hacker T Dog:

Hey I fancy some nutrients now cocker. It's tough work, this science lark. I could do with some meat paste down me face. I need to keep me energy levels up, I tells you. I can't function on thin air Barney.

Barney Harwood:

Well listen, I do sympathise a bit. But hang on just a little bit longer, because we've got to plan our next activity first and put it into action, is that okay?

Hacker T Dog:

Loo, I don't want any beef with you cocker. Do you get it? Beef? It's a sort of food stuff, isn't it? Let's get a plan on

Fran Scott:

This is why you're here, to keep it rolling with comedy. No, there's no beef Hacker. I think it's funnier when I say it. Anyway, stay there. I'm going to need your help in a minute. Now some of you have been in contact with us at Live Lessons. We've got a couple here to have a look at. Moyallon Primary School in Ulster, we had lots of fun painting our tongues blue, and are looking forward to the other experiments. Thanks for getting gin touch. And the next one, Mrs McGunnigle and Primary 7 from St Matthew's in Bishopbriggs, you've got the best name Miss. We loved doing the Supertaster experiment. We are now designing other experiments around taste to see if we can prove or disprove what we have read about different types of tasters. Thank you very much for keeping in touch with us. Keep them coming in. Now audience, remember those favourite foods that we spoke about earlier on? You wrote them down at the start. Get them ready because we're going to need them. Hacker, I think I know what yours is already, don't I?

Hacker T Dog:

Yes. You can read me like a cookbook, can't you?

Barney Harwood:

Quiche I imagine. That's not good. Okay.

Fran Scott:

Now, those of you watching from your classrooms, you should have downloaded activity sheet number one, and in the studio, inside of your packs you will find the same sheet. On this worksheet you will see a list of foods. Now working in pairs, we need you to analyse the list and place them in the correct groups. Write down which foods are high in protein, which ones contain lots of vitamins and minerals, lots of fats, lots of carbohydrates, etc, etc.

Hacker T Dog:

Hey, have you got any fibrous food on that list me old cocker? I'm feeling a little bit strained, if you get me drift. Has anyone got any brown rice or broccoli, that could loosen it up.

Barney Harwood:

Mate, it's all that meat paste clogging you up. You need more fibre in your diet.

Hacker T Dog:

The beauty of meat paste, it comes out looking the same as it went in.

Barney Harwood:

Well we need to make sure your digestion's healthier don't we, and, you know, your poo would be on the move if you had more fibre. We're going to grab some fruit and some wholemeal bread for Hacker, that should help things along nicely.

Hacker T Dog:

Thanks Barney.

Barney Harwood:

Now anyway, back to this favourite word that you wrote down earlier Have a think where it might fit. Teachers, don't forget to send in your class's thoughts please. We're going to give you a little bit of time to start working on it. How much time shall we give them Hacker?

Hacker T Dog:

Well I need a lot of time to get myself regular, but while I'm waiting, you've got 60 seconds to think and write, starting from now.

Barney Harwood:

Beautiful, off you go.

Barney Harwood:

We've got loads of answers here, haven't we? Beautiful. Okay, time is up. Stop writing. Fabulous. So we've got lots of guests here in the studio who have been analysing our food lists. Will, we're going to come to your first, what have you been writing down? Which section?

Will:

Carbohydrates.

Barney Harwood:

Okay, and what foods have you put in carbs?

Will:

Pasta.

Barney Harwood:

Pasta. Fran, are we right?

Fran Scott:

He is right. Pastas do contain a lot of carbohydrates. But as does the cereal and the brown bread.

Barney Harwood:

Okay, good to know, and there's your chart, so you can see where they fit. Beautiful. Maisie, what have you looked at?

Maisie:

I'm looking at vitamins and minerals.

Barney Harwood:

Okay, and what have you discovered?

Maisie:

That fruit will go in there, and milk.

Barney Harwood:

Fruit and milk for vitamins and minerals Fran.

Fran Scott:

That is exactly right. Fruit and milk, as well as vegetables and fish, they contain a lot of vitamins and minerals.

Barney Harwood:

And did you have a favourite food? A food that you wrote down earlier?

Maisie:

Yes.

Barney Harwood:

And what was your food?

Maisie:

Chicken.

Barney Harwood:

Chicken. And where do you think that goes on the list?

Maisie:

Protein?

Fran Scott:

Yeah, you are exactly right. Chicken is meat, and meat gives us lots of protein to help us repair our body.

Hacker T Dog:

Right, great Scott, where does my meat paste sit on that row? It's one of me favourite food stuffs cockers.

Fran Scott:

Well meat, meat paste, unfortunately is also meat, and so that means that it gives you lots of protein.

Hacker T Dog:

Yes, you don't get a coat like this eating fresh air Frank. You need meat paste, I'll tell you. Look at me, I'm a pedigree mongrel, look into my glossy old eyes.

Fran Scott:

You look beautiful.

Barney Harwood:

Yes, you are very beautiful Hacker.

Hacker T Dog:

Thanks cocker.

Barney Harwood:

Now some of you sent in your favourite foods, which we asked you to write down at the start of the show. So let's take a look. We've got Upton Meadows Primary School. Pizza is definitely a favourite in our class. Yeah, it's a classic, isn't it? What group's that in Fran?

Fran Scott:

Well it depends what you put on pizza, because the base can contain a lot of carbohydrate, but if you've got vegetables on it, that could contain vitamins and minerals, if you've got cheese, you can have your protein, so it just depends what you put on your pizza.

Hacker T Dog:

Stuffed meat paste crust I have.

Barney Harwood:

No, no, that's not what you put in your crust, that's gross. We've got one more to look at. English Martyrs School in Birmingham, some of us love a bit of cheese. That was sent with an accent that, wasn't it?

Fran Scott:

Yeah, some of us do love a bit of cheese, but the thing is cheese can be quite fatty. So cheese is a high fat food, but we still need a little bit of it.

Hacker T Dog:

Yeah, how do you eat your cheese cocker? Caerphilly.

Barney Harwood:

[LAUGHS] That was good. So now we know a little bit more about our favourite foods and the nutrients that they give us. We've got our completed chart here to have a look at. You can see that if you didn't have this filled in, that is what you could have done with it.

Fran Scott:

That is exactly right Barney. But there are some foods that fall into more than one food group. So if we have a look at the completed activity sheet one, you'll see for example that fish is both a protein, and contains vitamins and minerals. And vegetables are not only a source of vitamins and minerals, but they also contain fibre, which you like, don't you? So some foods have multiple roles helping us keep us healthy.

Food

A look at food groups and nutrients and why it is important to eat a balanced diet.

Your class will need this downloadable activity sheet:

Water and small intestine

Narrator:

So Fran, when it comes to eating we've learned what nutrients we need from certain foods, but what else do our bodies need to aid digestion when we've eaten, it's a very important question, with a very important answer. Now I wonder if our studio audience would be able to help us out here, what else do we need to aid digestion, hands in the air or shout it out if you think you know the answer.

Audience:

Water.

Narrator:

They all know the answer. Amazing so water Fran.

Fran:

Yes, well water is very important, it can do so many things for us, it help keeps our bodies at the right temperature.

Narrator:

Yes.

Fran:

It flushes out impurities like.

Narrator:

Poo poo.

Fran:

Like poo, yeah, it moves nutrients around the body and it also helps keeps us hydrated, otherwise we'd just shrivel up.

Barney:

OK so you can show us just how much water the human bodies made up of can't you.

Fran:

Yep.

Hacker T Dog:

Oh yeah ay, can you make a splash.

Barney:

Very good.

Fran:

Aw, I always make a splash because here we have a container and this represents a human body and I've made some markings on it, we've got one that's between 30 and 50 percent, one that's between 50 and 70 percent and another one between 70 and 90 percent, if you're watching in your classrooms, join in, you'll need Activity Sheet Number Two and working again in pairs, you have 15 seconds to choose how much water there is in the human body.

Barney:

OK we've got a countdown clock of 15 seconds, your time starts now.

Barney:

OK, time is up, so we asked you to choose how much water there is in the human body, lets have a look at the activity sheet again, who thought between 30 to 50 percent, hands in the air. OK, hands up if you think that the body is made up of between 50 to 70 percent water,

Fran:

Oh a fair few.

Barney:

A lot of hands there and hands up if you think it's the final one, between 70 to 90 percent.

Fran:

Oh, its sort of a split I think.

Barney:

I think it's a real split between the top two but I think, I think 50 to 70 just about had it I reckon, what do you think is that right?

Fran:

I think it was, if you did say between 50 and 70 percent of water, you are right.

Barney:

Yay.

Fran:

Well done.

Barney:

A little fist bump from the crowd.

Fran:

Yes, so imagine that this container represents your body and these bowls are the water, this is how much water you have in your body.

Barney:

OK.

Fran:

If I can get it all in. Oh we–

Barney:

You've spilt a bit.

Fran:

We've dropped one, its OK, that's a dribble, there you go.

Barney:

Hacker, I hope you're still observing over there and making notes about this. Hacker.

Hacker T Dog:

Ooh don't worry about what I'm doing cocker, just you remember in science you've gotta keep asking the quezzies.

Barney:

He's gone.

Hacker T Dog:

You I'll ask the quezzies, you just do the science.

Barney:

Listen I've just spotted meat paste on your lips, pay attention you, you're supposed to be a scientist. Um so right OK then I'll, I'll call them quezzies from now on shall I? Here's my next quezzie.

Hacker T Dog:

Quezzie, I say quezzie as my word.

Barney:

Alright so we've seen how much water we have in our bodies yes, but what does water do once its there?

Hacker T Dog:

Good quezzie Harwood.

Barney:

Thank you.

Fran:

Well I'd say it's a good question and to answer that question, if you follow me over here, I can show you exactly how it works because water is very important in our bodies, it keeps our bodies at the right temperature.

Barney:

Yes.

Fran:

It moves nutrients around the blood but it also helps move food through the digestive system.

Hacker T Dog:

Oh Fran oh.

Fran:

Now we are gonna look at a part of our digestive system called the small intestine, and by the time the food reaches the small intestine, its already been through the mouth and the stomach so its been broken down into tiny tiny pieces, ready to be taken up by the body and its water that's helped it get here, by keeping the food so soft that it can actually flow all the way through the system.

Fran:

OK.

Hacker T Dog:

He's no eyes, he's no eyes Fran, how can he find his food, he's no eyes.

Barney:

Hacker, don't worry it's a, it's a c-- it's a drawing, its not-- he's fine.

Hacker T Dog:

He's no eyes Barney.

Barney:

It's not a real person, he's OK.

Fran:

Yeah he does have no eyes or arms or nose.

Hacker T Dog:

How will he find his food?

Barney:

He's alright, don't you, listen you just you make notes. He is called Seymour by the way, the irony. Teachers, if you want to a discuss thing, in the best possible sense of the word discuss thing, uh demonstration of the digestive system, check out Activity Work Sheet 3 on our website uh, you can see how it works including how poo is made. Hands up if you wanna see how poo is made.

Hacker T Dog:

I'd like to know.

Barney:

Yeah pretty much everybody good.

Fran:

But we're not gonna look at that just yet, what we're gonna look at is the small intestine because once the small intestine, once the food is in the small intestine, the aim is to get as many of the nutrients absorbed into the blood as possible, and to show you how it does this, we need six volunteers, give them a big round of applause.

Barney:

As if by magic, here are our terrific scientific volunteers, Teachers, this is Activity Sheet Four, but if you watch how we do it first and then you can have a go yourselves. OK.

Fran:

Now you lovely volunteers, you are gonna be the lining of our small intestine, OK, which means in the middle is the small intestine, that's where all the food goes through. Now, the aim of the lining of the small intestine is to absorb as many nutrients as possible and our nutrients are gonna come from our audience, our audience have some balls, hold up your balls, lets see them. Now those are gonna be our nutrients and audience, you have got to throw them into the small intestine, which is this gap here, and we've got to see how many our volunteers can catch and so how many nutrients they can absorb.

Barney:

OK, so because they're a small intestine that's there job isn't it.

Fran:

That is totally their job.

Barney:

OK fine, good to go.

Fran:

So are you ready? And throw. OK how many can you catch? How many have we got, we've got one

Barney:

Two.

Fran:

OK this is.

Fran:

OK and stop. How many balls did we catch? We've got two.

Barney:

We got four.

Fran:

Four, OK it, it isn't a lot compared to how many went through but that is what would happen if our small intestine had smooth walls, but our small intestine doesn't have smooth walls, it has bits sticking out from the wall into the middle of the small intestine, and they're called villi and these bits which are sticking out, they basically may get in the way as the food travels through the small intestine, meaning that more of the food can be absorbed,

Barney:

Is that the villi there on the picture?

Fran:

It is, it is.

Barney:

Wow they're amazing.

Fran:

They are, they're amazing, they stick out and the slow the food down, so we're gonna try this again, but this time, you guys have got some nets and this means you're gonna stick them out into the middle, we're gonna throw the balls again and this time we're gonna see how many you catch, so grab your nets and audience are you ready? And throw the nutrients, lets see how many we catch, throw them into the middle. How many we got?

Barney:

We got loads. OK and time is up, thank you very much.

Fran:

OK, wow, we've got so many balls.

Barney:

So, well we only have four earlier on and I, I can see there's like, there's seven in just the front one so, we've got a lot more haven't we than we had before.

Fran:

We totally have now lets give a massive round to our volunteers, very well done you can go back to your seats.

Barney:

Thank you small intestines, what a great job.

Fran:

So, the small intestine does a pretty important job in the body, helping us absorb those nutrients from our food into our blood. Now it's a big job for believe it or not, a big part of the body, it might be called the small intestine but in fact the small intestine is pretty long, so long in fact that I'm gonna need you in the audience to help Barney unravel it.

Barney:

I can do it, I'm on my way. OK so if I come down, lets come down this one here, can you all stand up for me please, we need you to hold these small intestines, now you might notice that they're a bit thicker than normal ones, but they are the right length, so teachers, if you wanna do this in the classroom, can I squeeze through there do you reckon? We're gonna try and show how big these are. So if you wanna do this in the classroom, you can replicate this with a pair of tights or a pair of socks um and just stuff them with paper, you know what to do. Now, this is a six and a half metre long small intestine, its actually really hard to believe that we've got something this long curled up inside our bodies. Are we still going? Hold it up at the end for me, just grab the end, and if you stand up and hold it, perfect, there you have it, six and a half metres of small intestine, its huge isn't it?

Hacker T Dog:

Impressive that Harwood, it takes a lot of guts to digest food done it, do you get it? A lot of guts, I made a funny, thank you, I'm here for another ten minutes. Crack on Frank.

Fran:

I will crack on but, before we do, Hacker, you've been observing the lesson, can you, can you give us a bit of an update on where we're on so far.

Hacker T Dog:

Course I can me old cocker yes cough cough, here is my terrific scientific update, so far I have written down the quezzies, what happens when we eat with the help of my mate Professor Blissett I have observed the results of the kale and raisin experiment and noted the bitter and sweet changes that can occur in a science experiment plus I have analysed what nutrients you need to function, I have written, observed and analysed the three scientific boxes ticked and updated. I thank you Frank.

Fran:

Aw I thank you Hacker, that was a fabulous update.

Water and small intestines

Fran Scott shows us why water is important for digestion and how the small intestine works.

Your class will need these downloadable activity sheets:

Energy in food

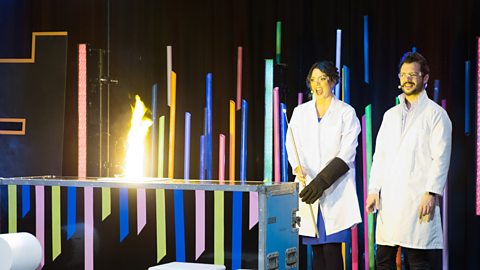

Fran Scott:

So we know we need nutrients and water, and that different foods can take different amounts of nutrients, as we saw in the food groups that you filled in earlier. And to show you this in detail, I could bring you a fancy diagram, or a film that shows the internal workings of our bodies. Or we could set something to fire and see what happens.

Hacker T Dog:

Oh things are going to heat up here [UNSURE OF WORD] I can feel the temperature rising. Either that or I'm getting a bit clammy cause of Sue.

Fran Scott:

[LAUGHS] It is a little bit clammy in here, it's got to be said. But we're going to have some fun. Let me show you what we're going to do. Over here I have some oxygen. Now this oxygen is not as a gas as we usually find it, but it's actually a liquid. It's been liquified. And the process to do this has made it very cold, so cold that I've got to be careful handling it, and that's why I've got my gloves here And also I've got two different foods. I've got some spinach and some cheesy puffs. And the same weight of each of those.

Hacker T Dog:

Hey Frankie, are you going to cook them? Can I have mine slightly charred please, with some ketchup on the side cockle? I'd love that? Do you want some Sue. Oh yes, I'll have the same please. Oh thanks Sue.

Fran Scott:

Hacker I'm rubbish at cooking, so I'm really not going to cook them as such, but I am going to set fire to each one. But there's a purpose to all of this. What we're going to be doing is observing the food as it burns, because it is the food that is burning. The oxygen is going to help with this. And as each one burns, I want you guys to observe what happens to the flame, how big it is, and how long it lasts. But to help me with this, I need a beautiful assistant. But I couldn't find one, so instead I've got Barney.

Barney Harwood:

Hey, what a fantastic introduction. [APPLAUSE] Thank you.

Fran Scott:

Oh look at you, you've got your fans in the audience.

Barney Harwood:

Yep, I told them to do that. I need my burn stick, don't I?

Fran Scott:

So what we're going to do is you're going to get ready.

Barney Harwood:

Yeah, I'm ready.

Fran Scott:

You're going to be my lighting assistant. So I'm going to pour on…

Barney Harwood:

Right up my street this it.

Fran Scott:

My liquid oxygen onto the spinach. There we go.

Barney Harwood:

I'll put this away for a little bit.

Fran Scott:

I think I've got enough on there.

Barney Harwood:

Okay.

Fran Scott:

I'm going to get rid of my oxygen before we get burning.

Barney Harwood:

The splint is going.

Fran Scott:

Thank you very much.

Barney Harwood:

Are you ready?

Fran Scott:

Yeah, let's see if we can set this on fire.

Barney Harwood:

Okay… It's not bad is it?

Fran Scott:

There we go, there we go. So it's burning away.

Barney Harwood:

It wouldn't keep you warm in the winter time, would it really?

Fran Scott:

It wouldn't. Now the thing is, spinach, it's not producing a massive fire because it doesn't contain many calories. It doesn't have much energy in it. But it does have lots of vitamins and minerals. And what we need in our body, we only need a certain amount of calories, but we need loads of vitamins and minerals. Right?

Barney Harwood:

So are you saying don't eat spinach because it's got no calories in it.

Fran Scott:

No, I am saying eat lots of spinach because it's got not many calories, but it's got lots of vitamins and minerals which is what our body needs.

Barney Harwood:

Sorry, I tried. I did try. But she's not having it.

Fran Scott:

He did try, he did try. But instead, what we're now going to try are our cheesy puff

Barney Harwood:

Yes.

Fran Scott:

Right, so here we go, I'm just going to get rid of this. And again we're going to pour on the oxygen, and we'll just see if this produces a different kind of flame. One that's maybe bigger or smaller, different size. Let's pop this oxygen on.

Barney Harwood:

This is going to be fun.

Fran Scott:

There we go.

Barney Harwood:

Okay, we're burning.

Fran Scott:

Okay. We're burning, we're good. Let's go in for the fire. Okay, in we go.

Barney Harwood:

Oh yes, look at that.

Fran Scott:

There we go.

Barney Harwood:

Whoa.

Fran Scott:

[LAUGHS]

Barney Harwood:

That's amazing.

Fran Scott:

It's, it is pretty good, and it's so much bigger because the cheesy puffs have so many more calories in. They have fat, but not as many vitamins and minerals, and that's why we can't eat as many cheesy puffs as we can spinach.

Barney Harwood:

So in conclusion, eat loads of cheesy puffs because they've got loads of energy in them.

Fran Scott:

It's the opposite way round Barney.

Barney Harwood:

I tried again. I'm sorry. Listen, don't try that at home kids or teachers, we've got all the kit here that's been brought in specifically for that experiment. Hacker, did you like that?

Hacker T Dog:

Bit overcooked for me cocker. That was smoking, wasn't it Sue? Yeah, I liked that.

Fran Scott:

Yeah, there's not much left.

Hacker T Dog:

Now don't try that at home cockers, oh this science lark today is flaming amazing, isn't it? In fact it's terrific scientific, don't you know?

Energy in food

Fran Scott shows us the energy content of different foods in a fiery demonstration.

Your questions answered

Fran Scott:

Hello there and thank you for watching the 'Live Lesson'. Now Professor Jackie Blissett: and I, we have hung around a little bit to answer some of your questions that we didn't quite get through in the 'Live Lesson'. So, let's have a look at question number one.

Fran Scott:

Why are the twins in our class different types of tasters? And that's from Quinton Church Primary School in Birmingham.

Fran Scott:

So, Jackie, over to you.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Well, I think it's probably the case that the twins in this class aren't identical twins. They're probably more like the siblings so we know that there are genetic effects on our number of fungiform papillae, but there's also a whole host of environmental effects on whether or not you like certain tastes or not.

Fran Scott:

Fair enough. Ok. Let's go on to the next question.

Fran Scott:

Why, when you are not well, do your taste buds appear to stop working? And that's from Aimon from West End Academy in Hemsworth.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Well, this is a really interesting one because we talk about taste and in our 'Live Lesson,' we talked about the fact that our sense of flavour is not just about what goes on in our taste buds. There's also a whole host of other things, but particularly what happens in our noses. So, smell is really important. So, when you've got a cold or that kind of problem that might block up your nose, it can really effect what you think of as your sense of taste. It's actually the flavour of the foods is a little bit impaired.

Fran Scott:

And it's just basically because you have a little bit more snot, don't you? And so it's blocking those receptors being able to get those flavour in. So that's a very snotty question. So, let's have a look at the next one. What have we got? Is it possible to damage your taste buds? How? And that's from Good Shepherds RC Primary School.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

It is possible to damage your taste buds. Yes.

Fran Scott:

How would you do that? I was, like, I don't know.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Yeah, well one of the things that's quite a common way of doing it is having a really, really hot drink. So, a drink that is too hot can damage your taste buds.

Fran Scott:

And by hot, you mean temperature hot?

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Yes, exactly. Not spicy. So, yes, when it's just a little bit too hot and you drink it, you can damage those taste buds. But you don't need to worry, taste buds renew themselves pretty regularly. So the average set of taste buds last for about ten days. So they repeatedly are renewing all the time.

Fran Scott:

I like that. That's quite convenient. So, if you damage them, don't worry. In about two weeks you'll be absolutely fine.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Yeah, exactly.

Fran Scott:

Fair enough. Next question.

Fran Scott:

Would it make any difference if we ate something strong before we tested our tongue? And that's from Bollington Cross Primary School.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

It wouldn't effect the number of fungiform papillae that you can see on your tongue, but they are absolutely right that if you taste something really strong, what you taste afterwards can be effected by that. So if you've tasted something, or perhaps it's got a lot of chilli in or it's a very, very strong flavour, that can make your taste buds very temporarily a little bit less sensitive.

Fran Scott:

So, if they ate something strong before they were part of the experiment in terms of the kale and the raisin, yet it could effect it, but in terms of testing the tongue for the number of fungiform papillae, it wouldn't have an effect.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Exactly.

Fran Scott:

Fair enough. Alright. Next question.

Fran Scott:

What happens to food when it is in the stomach? And that's from Ava at St Elizabeth's School.

Fran Scott:

I'll take this one. You can step in. So, in terms of in your stomach, it's all about breaking the food down because in the small intestine, which is after the stomach, you could only absorb food is so tiny, tiny, beyond microscopic, and so the stomach helps to break down the food into those tiny, tiny pieces. And it does this with things called enzymes. And enzymes, they help to break down all the different types of food into these tiny pieces. So, eventually you can get them into the blood. And that's about, yeah, there's more detail but that is the summary of what the stomach does. What's the next question?

Fran Scott:

What is the best way to record results? And that's from West Jesmond Primary. Good question.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

That's a really good question because whenever we're doing any kind of science, we want to be really accurate with our observations. So it's always great to write down things immediately, as soon as you've observed them and making sure that you've got, perhaps, other people checking what you're doing. So you get two people, you can compare how well you're both doing in terms of the quality of your data.

Fran Scott:

But I suppose it's in terms of the method of recording them. Is pen and paper the best? Is on a computer? Is by just talking?

Professor Jackie Blissett:

It can be whatever works for whatever study you're doing at the time. So, in our experiment with the children in the four different schools, some of them recorded all of their data using iPads and other electronic media and some of them used pen and paper. It depended what worked best in their particular classrooms.

Fran Scott:

Makes sense. Hope that answers your question. Let's have a look at the next one.

Fran Scott:

Is it true that certain parts of our tongue are better at tasting different flavours, like sweet, sour and bitter? And that's from Bishop Winnington-Ingram Primary School in Ruislip.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Yes, so this is quite a common myth. So you'll see a lot of pictures that show different areas of the tongue that are particularly sensitive to one type of taste or another. And it's not as true as we previously thought. So it's certainly the case that we have most of our fungiform papillae, so a lot of our taste buds, are focused on the front of our tongues. Obviously because it's important for us to taste things quite quickly, but it's not particularly true that one area only has a sense of one taste. So our sense of taste is distributed across the tongue.

Fran Scott:

Do you know why it came that a lot of the old diagrams show it to all be separated into different regions?

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Well I think there are certain areas of the tongue, for example at the back of our tongues, there are some cells that are particularly sensitive to bitter tastes, for example. But that doesn't mean that the front of the tongue can't taste bitter as well. So, it's just one of those things that was over-simplified, I suppose.

Fran Scott:

Fair enough. So you can taste all tastes in all part of your tongue. Ok, let's have a look at the last question.

Fran Scott:

As a girls school, we are inspired by other female scientists like you. What advice would you give us? And that's the Red Maids' School. Jackie, I will let you take this question. I might finish it off for you, but we'll see.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Ok, well, that's really fabulous to hear. We need lots of girls to be more excited about science and get involved in it as a career. What I would recommend to you is you find something that you're really interested in. It doesn't matter what it is. It could be chimpanzees. It could be taste. It could be water. It could be anything and just find out more about it and keep on finding out more about it. You gradually learn where the gaps are in our knowledge and you can then design experiments to find out what might the answers be for those gaps.

Fran Scott:

Exactly, and I would say you don't have to decide what job it is that you're going into. You might think, I like science, do I have to decide now if I want to be an engineer or a doctor or a vet? No, because by the time you guys are getting jobs, jobs are gonna exist that you don't even know about yet. So I would say, just like Jackie, do the thing you enjoy, not necessarily aiming towards a certain, but do the type of science you enjoy and then eventually a job will exist in that type of science. I never dreamed that I would be paid to do experiments on television and to explode cheesy puffs on television, but now I'm paid to do that. So do the things that you enjoy, and you'll get a job in it because you'll be good at it, because you're good at the things that you enjoy.

Fran Scott:

So, I think that brings us to the end of our questions. Thank you very much, Jackie, for answering and thank you very much for watching. Goodbye.

Professor Jackie Blissett:

Pleasure.

Your questions answered

Science presenter Fran Scott and Professor Jackie Blissett answer your questions.

Watch the full Live Lesson

If you enjoyed these clips, why not catch up with this Live Lesson and learn more about the science of taste and food here.

Primary Live Lessons

Find out more about our Live Lessons designed for primary school students

Live Lessons homepage

Return to the Live Lessons homepage for more curriculum-linked Live Lessons across primary and secondary