Introduction

In Europe, using human bodies for medical study was banned or limited for centuries for religious and social reasons.

To practice their anatomy skills, doctors were largely limited to dissecting the bodies of executed criminals. As more medical schools developed, the demand for bodies grew and could not be met by the number of executions. When bodies became scarce, some people took to stealing bodies from graves, or worse, to sell to medical schools.

In 19th century Edinburgh, two enterprising men did just that. Their names were William Burke and William Hare.

Dissection

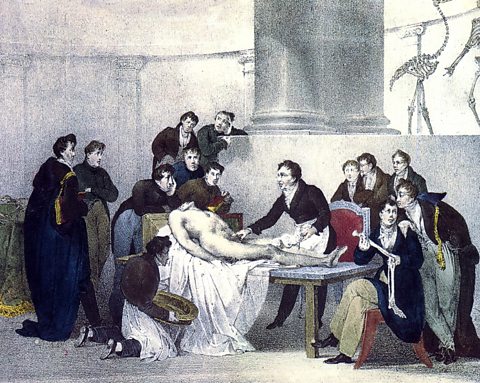

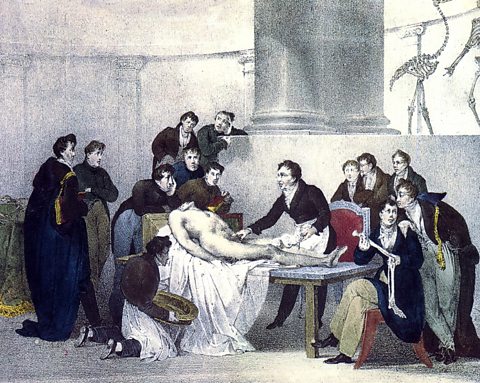

DissectionDissection is the medical process of opening up a body to observe the inner structure of things such as the organs, muscles, and skeleton. of the human body to learn about anatomy and disease was practised by the Greek physicians Herophilus (335 - 280 BC) and Erasistratus (305 - 250 BC) in Alexandria in what is now Egypt. But practical study of the human body fell out of favour for hundreds of years.

The Renaissance period brought new interest in anatomical study. Leonardo da Vinci produced a series of drawings of the human body while dissecting an old man who had died in a hospital in Florence in the winter of 1507-08.

The growth of medical schools led to a demand for bodies to dissect and learn from. However most people in Europe did not want their own body, or those of their loved ones, to be dissected rather than given a Christian burial.

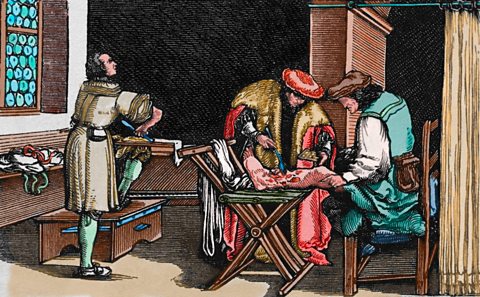

A solution was to use the bodies of those who were seen not to deserve a Christian burial. In 1505, a law was passed that gave the Incorporation of Surgeons and Barbers in Edinburgh the bod of one executed criminal per year. In 1540, a similar ruling gave the Companies of Barbers and Surgeons in London, the right to dissect the bodies of four executed criminals each year.

This meant that bodies for dissection were rare – and that there was always a shortage.

The need for corpses

In 1751, the British Government passed The Murder Act. The act was designed to be a deterrent to would-be murderers. As well as being swiftly executed, the act also denied murderers the right to a burial.

Instead, their bodies were handed over to medical schools to help advance the knowledge of trainee doctors through dissections.

…in no case whatsoever the body of any murderer shall be suffered to be buried; unless after such body shall have been dissected and anatomized.

–

Even after the Murder Act, the supply of bodies to the medical profession in Scotland was low. Between 1752 and 1800 there were only 43 criminals were sentenced to dissection in Scotland. The number was low in Scotland where there were a total of 50 crimes that carried the death penalty.

More bodies were available elsewhere in the UK - in England and Wales more than 200 crimes carried a mandatory death sentence. However in 1823, Parliament passed the Judgment of Death Act which removed the punishment of death from a long list of crimes. This reduced the number of corpses that doctors had access to even more.

In desperation, many medical schools were prepared to pay good money to anyone who could supply them with fresh corpses.

Resurrectionists

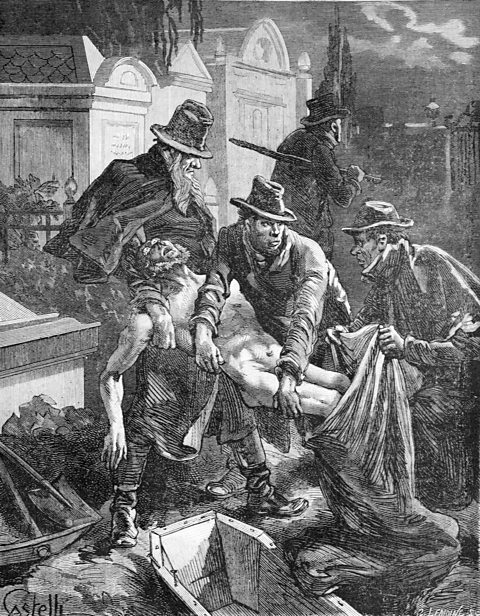

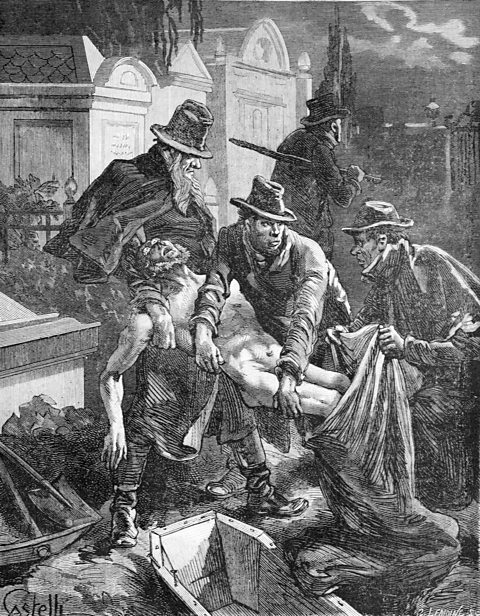

With high demand for bodies – and a lot of money on offer – some people turned to digging up the bodies of the recently dead and selling them to medical schools.

Under the law at the time, buried bodies were not seen as property, so Resurrectionists (as they became known) were able to dig up bodies without fear of being arrested for theft.

Freshly buried bodies would be dug up and, under great secrecy, be sold to medical schools and private doctors.

Was bodysnatching a crime?

Grave robbing or bodysnatching were not crimes.

According to common law, a dead person could not be treated as property. And because a body wasn't property, that meant it could not be stolen.

In Scotland, some grave robbers were charged with stealing if they took jewellery or other belongings from a coffin along with the body. But taking the body itself was not against the law.

It wasn't until 1998 that anyone in the UK was successfully prosecuted for stealing human remains and this was only because the body parts taken had been preserved and exhibited at the Royal College of Surgeons.

The Court found that

human body parts are capable of being property…if they have a use or significance beyond their mere existence…if for example, they are intended for use in an organ transplant operation, for the extraction of DNA or, for that matter, as an exhibit in a trial.

Body snatching became so commonplace that families would go to great lengths to protect the bodies of their loved ones:

- in Scotland in particular, mortsafes - iron cages that surrounded graves - were used to make it more difficult to remove the body.

- watchtowers were built in churchyards and cemeteries so they could be guarded at night.

It was particularly important for families to watch over the graves of their freshly buried relatives, as ‘fresher’ bodies were worth more.

In time, some body snatchers turned to murder in order to get the freshest bodies possible.

Edinburgh - with many prestigious medical schools - was host to some of the most infamous examples of these type of murders.

How much did a corpse cost?

In the 1828 Select Committee on Anatomy, a doctor stated that corpses could cost between two and eight guineas.

A guinea was a gold coin that was worth twenty-one shillings. A single shilling was the daily wage for a workman or labourer so a fresh corpse in good condition could be worth the equivalent of several months worth of pay!

The equivalent price today would be anywhere between £150 - £1,000.

Burke and Hare

William Burke and William Hare were originally from the north of Ireland and came across to Scotland as Navvies'Navvie' was the abbreviated nickname for navigator. Navvies were the workmen who dug and constructed canal and railway lines. on the Union Canal.

The two met in Tanner’s Close in the West Port area of Edinburgh. Hare was running a boarding house there and the two men struck up a friendship.

Their journey into the world of anatomy murder was not intentional at first.

One of Hare’s elderly lodgers, an army pensioner known as Old Donald, died of natural causes, leaving a debt of £4 in rent (roughly £271 today).

To cover the cost of this debt, the two men decided to sell the pensioner's body.

To fool the authorities, they weighted Old Donald’s coffin down with bark and took his body to Professor Robert Knox who ran a private anatomy school at Surgeon's Square in Edinburgh.

Knox did not deal with Burke and Hare directly. The pair were paid £7 10 shillings for Donald’s body – that's roughly £508 in today's money.

Murder

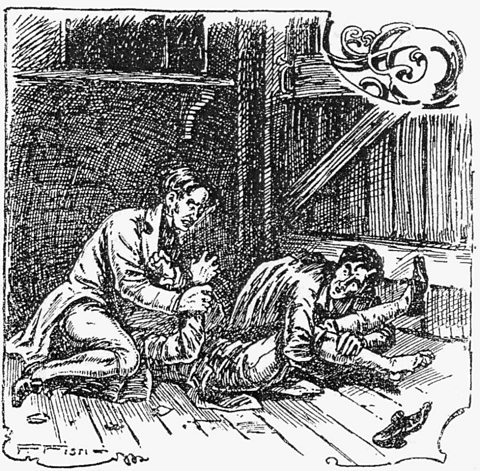

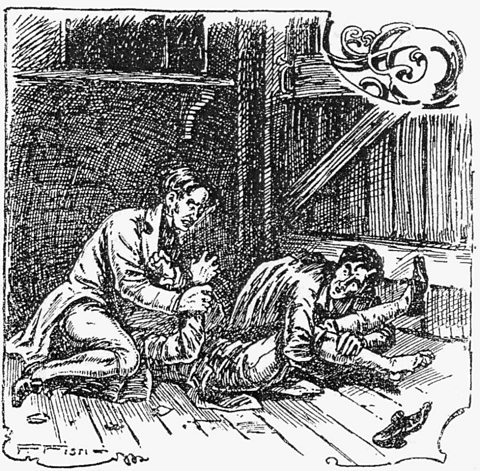

As they could not rely on their tenants becoming ill, Burke and Hare turned to murder as a source of bodies for sale.

Many of their victims were lodgers at Hare's house. Others were invited to the house and plied with alcohol until they fell asleep or were unable to defend themselves. They were then smothered before being packed into a tea chest, transported to Surgeon's Square and sold to Knox.

In total it is believed that they killed 16 people.

With their continued success, the pair became more careless in their choice of target. James Wilson was a young man who lived on the streets of Edinburgh, supporting himself by begging. He was a recognisable figure as he had a clubfoot which caused him to limp.

After Wilson was killed and his body sold to Knox's anatomy school, some of his students said they recognised the body. When it became known that Wilson was missing, Knox is said to have removed his head and feet before the dissection took place.

Capture

Burke and Hare’s partnership was not to last – the two fell out over a disagreement that Hare was trading with Knox on his own and cutting Burke out of the deals.

This resulted in Burke taking on his own lodgers and this ultimately led to their downfall and capture.

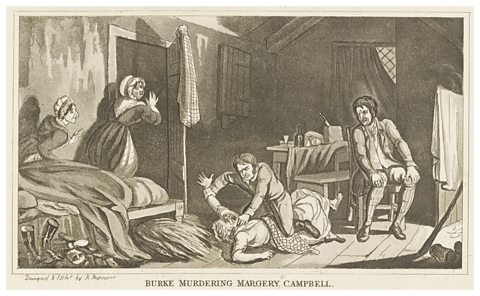

On Halloween 1828, Burke asked his lodgers to stay with Hare for a night as a ‘distant relative of his mothers’ was coming to stay. The ‘distant relative’ was Margery Docherty and she was to be the pairs’ last victim.

When Burke’s original lodgers returned to collect some items they had left behind, they were refused entry to retrieve them - they later broke into the room and discovered Marjory’s dead body.

They reported the murder however by the time the police arrived the body had already been sold to Professor Knox.

Trial and punishment

Both men were arrested and quickly turned on each other.

As the story hit the press, friends and family of the victims came forward to identify their clothes. However, without the bodies there was simply not enough proof to charge the pair.

This was the case until the Lord Advocate, Sir William Rae, offered Hare immunity to testify against Burke. Hare agreed and the trial began on Christmas Eve 1828.

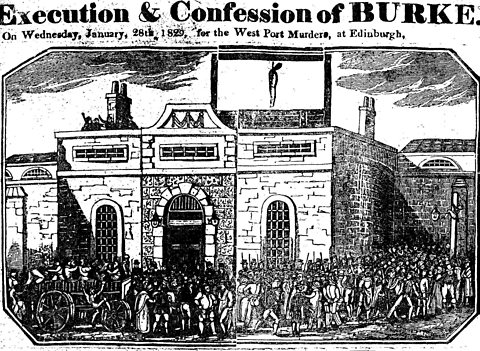

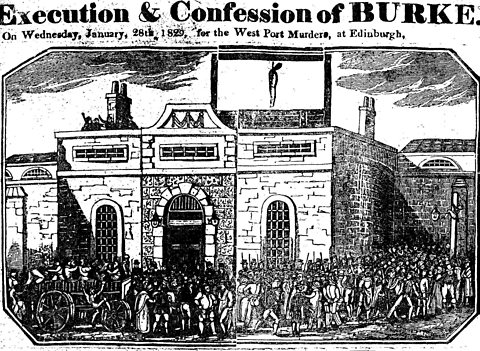

Burke was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging.

He was executed at the Lawnmarket in Edinburgh on 28 January 1829 and his body was given to medical science to be used for dissection in anatomy lessons. His skeleton can still be seen in the Surgeon’s Hall in Edinburgh today.

Hare was released and left Edinburgh. It is not known exactly what happened to him and how he ended his days.

Professor Knox was cleared of all involvement as he had not dealt with Burke and Hare directly and was able to claim that he did not know where the bodies came from. However he was forced to resign his position as curator of the Royal College of Surgeons' museum and was later expelled from the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Aftermath

The murders committed by Burke and Hare in Edinburgh inspired others to murder for profit.

The most notable case was committed by a gang of men who became known as the London Burkers.

Like Burke and Hare, these resurrectionists also resorted to murder to provide medical schools with fresh corpses.

The scandal of these types of murder led to the government passing the Anatomy Act of 1832.

This provided doctors, anatomy lecturers and medical students with greater access to dead bodies from prisons and workhouses. It also allowed the public to donate their bodies to medical science.

This act effectively brought an end to the bodysnatchers' trade.

Test your knowledge

More on Medicine through time

Find out more by working through a topic

- count7 of 8

- count8 of 8

- count1 of 8

- count2 of 8